Code Nation Excerpt (Chapter 1)

Is computer programming a popular movement?

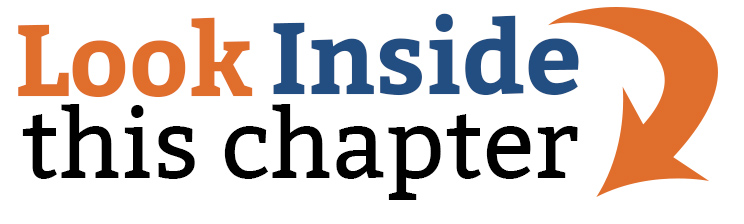

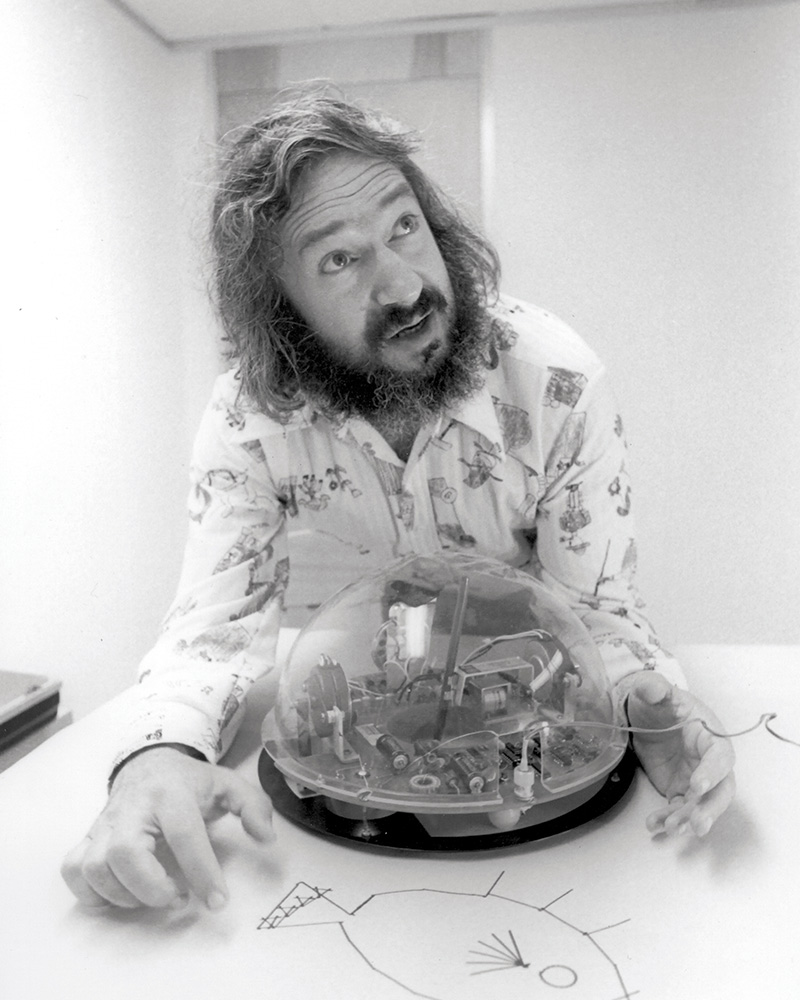

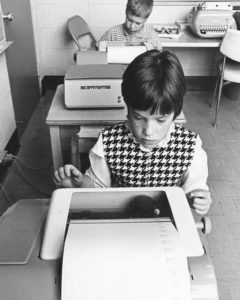

American school children experiment with programming using teletype machines (1970s). (Courtesy of the Computer History Museum)

How have people learned to write computer programs in the past, and how have the experiences of programmers changed over time?

Are there long-term benefits to learning how to program? If so, how should communities teach programming skills to their citizens?

These are some of the questions that animate the chapters in Code Nation: Personal Computing and the Learn to Program Movement in America. The book begins with a discussion of what programming is, and how computer scientists, historians, and educators have tried to evaluate software and programming systems in the past.

The book then surveys a variety of historical computing platforms, and argues that the push to learn programming and teach it systematically has been a social and cultural movement of major significance since at least the 1960s.

What are the characteristics of the learn-to-program movement and why does it matter?

As an expression of computer literacy, the movement has sought to make computers more understandable, imprint useful technical skills, establish shared values, build virtual communities, and offer economic opportunities for a wide range of technology enthusiasts.

The learn-to-program movement has supported user communities, schools, and emerging commercial industries, many which have benefited greatly from the utility provided by digital electronic computing. The end result of this movement has been nothing less than a globally-connected society that is saturated with computer technology and enchanted by software and its creation—a Code Nation.

But the movement has been costly, and it has generated its share of political controversies. Considering the costs and the effort required, does it really matter who learns to program and who does not?

Code Nation argues that the people we choose to learn programming skills matters a great deal. There are, and have been, clear inequalities in our technical education systems.

For example, an analysis of the recent past indicates that African-American and Latino children are much less likely to receive computer training in American schools than white or Asian children. When scholars analyze gender disparities and later professional outcomes, they find that only two out of ten information technology (IT) professionals are women in the current U.S. workforce.

One important outgrowth of this research has been the rise of not-for-profit organizations that teach young people how to program, including Code.org, Black Girls Code, Girls Who Code, Native Girls Code, and The Hidden Genius Project. At the high school level, many organizations focus on introducing programming concepts and preparing students to take the College Board’s AP Computer Science Principles examination. I evaluate the work of Code.org and the Hour of Code movement near the end of this book. As a preview, I note that Code.org has completed over 720 million introductory programming sessions since the organization began in 2013, with 46% female and 48% underrepresented minorities currently using the group’s courseware.

These figures are clearly impressive, and they show one way that creative thinking and industry partnerships can support an education system that is struggling to find resources and leadership. However, the new initiatives were not created from whole cloth, but are simply the latest manifestations of a long programming literacy movement that has a fascinating history and is now being scaled to meet global needs. Just as in the past, there is an ongoing debate about the efficacy of wide-ranging computer literacy programs and the best way to deliver them.

Understanding the long history of the learn-to-program movement and its cultural commitments will teach us important lessons. Our world is increasingly dependent on computers and technology, and it is imperative that we work together to understand the characteristics of technical communities and how they shape our hearts and minds.

Michael Halvorson, Ph.D., is an American technology writer and historian. He was employed at Microsoft Corporation from 1985 to 1993, where he worked as a technical editor, acquisitions editor, and localization project manager. He is currently Benson Chair of Business and Economic History at Pacific Lutheran University, where he teaches the history of business and computing and directs the university's Innovation Studies program.