Code Nation Excerpt (Chapter 6)

In the 1980s, computer programmers contributed to numerous cultural and intellectual movements

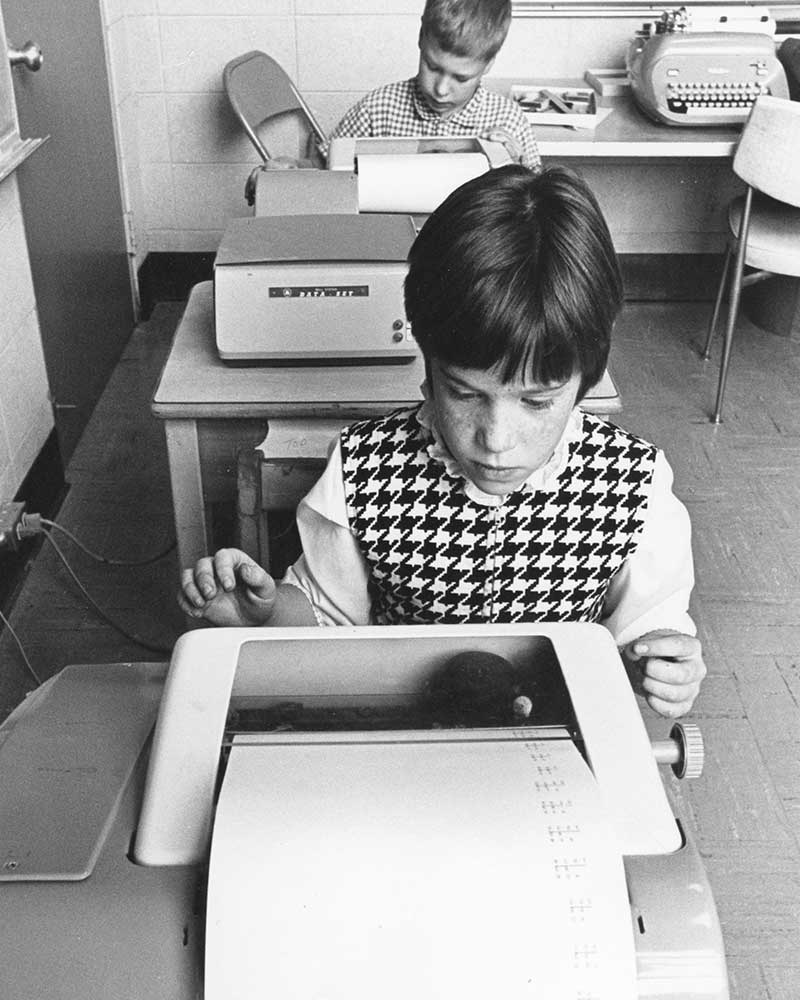

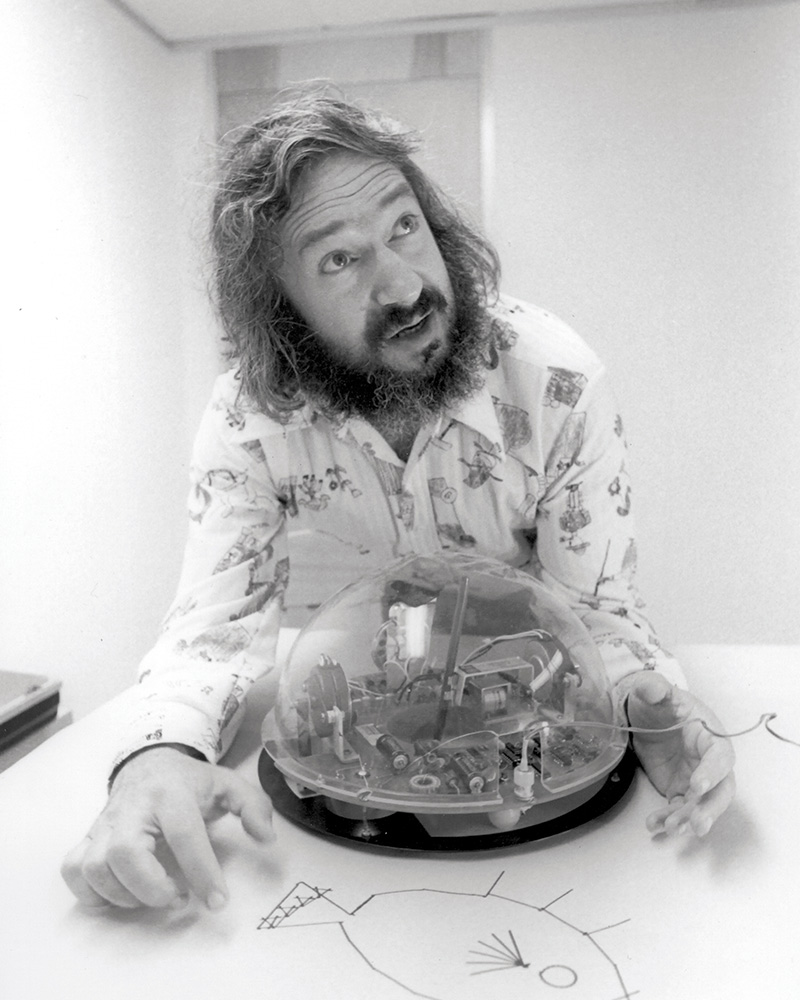

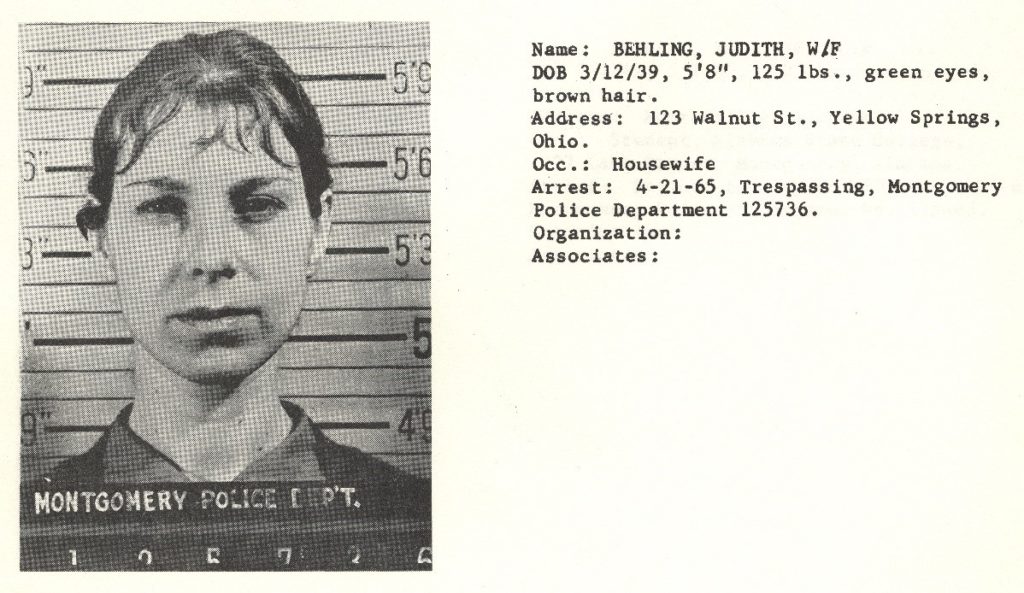

Judith Behling police photo, Montgomery Police Department, 1965. Courtesy Alabama Department of Archives and History. (Individuals Active in Civil Disturbances, Vol. 1.)

This chapter examines the contours of America’s PC programming culture with an assessment of a group that is sometimes held at arm’s length from polite computing society—the activists and illicit users known colloquially as hackers, phreakers, cyberpunks, and cypherpunks.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, many computer users and virtually all security specialists feared hackers—often for good reason. In fact, this iconic subgroup has existed since at least the 1960s, holding positive and negative stereotypes in the popular imagination.

In sociological terms, illicit users all speak from relatively marginal positions in computing society. They respond to, and protest against, the dominant social, technical, and economic structures that emerged in the U.S. in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s. Code Nation suggests that marginalized voices within a subculture are important for historians to appreciate if we want to assess the comprehensive structures in society that control and delineate power relationships.

Judith Milhon: From Civil Rights Activist to Cyberpunk

Although most published studies about illicit users emphasize male agents, there are important exceptions to this stereotype. One important example featured in this book is Judith Milhon (1939–2003), commonly known as St. Jude. Milhon was a self-taught programmer who became an important advocate for civil rights, as well as a writer, editor, and advocate for women in computing.

Judith Elaine Milhon was born on March 12, 1939 in Anderson, Indiana. She attended schools in Indiana and married Robert A. Behling in 1961, taking his last name. Attracted to the nascent countercultural movement, Judith Behling moved near Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, and established a communal household there with her husband, young daughter, and a growing collection of friends.

In March 1965, Behling and her friends decided to engage more directly with the civil rights struggle, and they participated with Martin Luther King, Jr in the landmark voting rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. The protests gained momentum, and in the following month Behling was arrested for trespassing in Montgomery. On her intake form Judith was listed as a “housewife” from Yellow Springs, Ohio.

A little later, Behling was arrested for civil disobedience in Jackson, Mississippi, and after this arrest she served jail time. Behling’s activist run-ins with the authorities greatly influenced her views and they solidified her reputation as an advocate for civil rights and free speech.

Behling’s High-tech Career

Judith Behling started programming in 1967 after reading a book on FORTRAN. After learning the basics, Behling took a job as a programmer for the vending machine firm Horn & Hardart in New York City.

In 1968, Judith Behling moved to the San Francisco Bay Area with friend Efrem Lipkin, and her daughter, Tresca Behling. Judith separated from her husband and thereafter went by the name of Jude Milhon. Soon after relocating, Milhon worked at Berkeley Computer Company (BCC), an outgrowth of Project Genie, and she helped to implement the communications controller of the BCC timesharing system.

Milhon thrived in the Berkeley area and soon met other people who shared her interests in computing and activism. During the Summer of 1968, Milhon met Lee Felsenstein, a local engineer and long-time political activist, and Milhon soon introduced Felsenstein to Efrem Lipkin, her long-term partner. In the early 1970s, the three partnered on various projects, including the Community Memory project in Berkeley, a social networking experiment described in Chapter 2 of Code Nation. This group came to have a tremendous influence on early personal computing and the development of future networking systems.

Milhon later turned to journalism as an outlet for her ideas about computing and social activism. In the mid-1980s, she contributed to the counterculture magazine High Frontiers, founded in 1984 by Ken Goffman, a skilled editor and writer who used the pseudonym “R.U. Sirius” in print. The magazine was also based in San Francisco and it had a strongly counterculture outlook. For example, it creatively explored the local fringe community on topics related to technology, drugs, sex, and social issues.

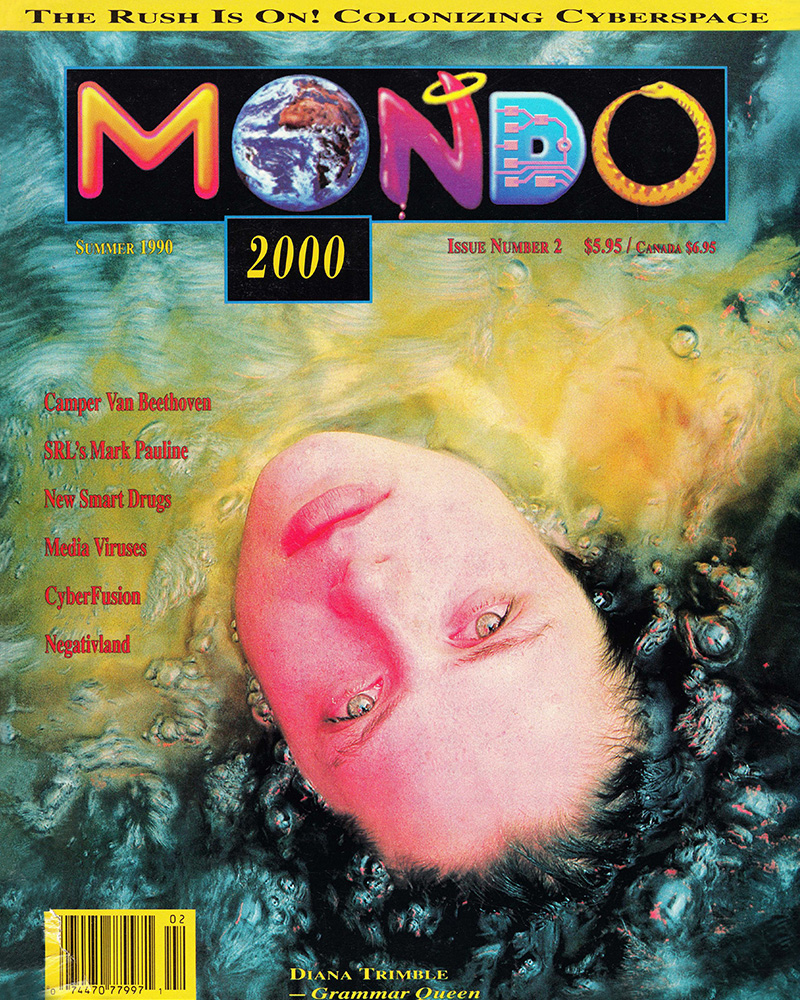

In 1988, High Frontiers changed its name to Reality Hackers, a title that more clearly emphasized the growing synthesis among programming, hacking, and psychedelic cultures. Milhon formally joined the magazine as Editor-in-Chief, taking the pseudonym “St. Jude” to emulate the public posture of the leading editors and contributors. In 1989 the magazine reorganized, changed its name to Mondo 2000, and St. Jude became an associate editor and contributor of interviews and essays. She also spent time encouraging users and programmers in the emerging online world of modems, bulletin boards, and distributed computing.

Mondo 2000 was an astonishing publication for its era, helping to give birth to a creative expression called cyberpunk culture, a futuristic, science fiction aesthetic that interposed hacking, high technology, drug use, sex, anarchy, and goth sensibilities. In 1991, St. Jude was promoted to Managing Editor of Mondo 2000, and she began a regular column entitled “Irresponsible Journalism,” which became her most recognizable publishing platform.

Much more about the career and writings of St. Jude can be found in Chapter 7 of Code Nation. The chapter also explores the career of other notable hackers and the cultural influence of publications like Reality Hackers and Mondo 2000.

Michael Halvorson, Ph.D., is an American technology writer and historian. He was employed at Microsoft Corporation from 1985 to 1993, where he worked as a technical editor, acquisitions editor, and localization project manager. He is currently Benson Chair of Business and Economic History at Pacific Lutheran University, where he teaches the history of business and computing and directs the university's Innovation Studies program.